The basic components of our solar electric system are:

- 1250 watts of solar panels (10 100-watt panels and 5 50-watt panels)

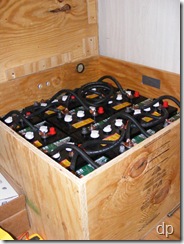

- 12 6-volt 225 amp hour batteries

- 60 amp MPPT solar charge controller (Xantrex XW-60)

- 3,000 watt true sine wave inverter (Aims Power)

- 600 watt true sine wave inverter (Samlex)

I bought the panels and batteries from Sun Electronics in Florida. The panels are Sun-100 and Sun-50, panels that the company has assembled for them from other panel manufacturer’s parts. These are not top of the line panels, but I didn’t pay the $3 to $5 per watt price of top of the line panels. I bought these because they were on sale ($1.74 per watt – they now have other sizes on sale for the same price), fit within my budget, and their specifications were appropriate for my application. They look fine and test fine on my digital multi-meter. Maybe they won’t last as long as other name brand panels, but they seem like a good place to start.

I bought the panels and batteries from Sun Electronics in Florida. The panels are Sun-100 and Sun-50, panels that the company has assembled for them from other panel manufacturer’s parts. These are not top of the line panels, but I didn’t pay the $3 to $5 per watt price of top of the line panels. I bought these because they were on sale ($1.74 per watt – they now have other sizes on sale for the same price), fit within my budget, and their specifications were appropriate for my application. They look fine and test fine on my digital multi-meter. Maybe they won’t last as long as other name brand panels, but they seem like a good place to start.

The batteries are 6-volt golf cart batteries, a common deep-cycle lead acid battery for solar  applications, especially new systems. They are relatively cheap and should provide several years of service if treated properly. One of the things I didn’t realize when I first ordered the panels and batteries is how the solar array needs to be sized to the battery bank. You can have too large of a battery bank for the number of panels which isn’t good for the batteries. I actually was on the bottom edge with my amount of PV (photovoltaic) watts with our original number of panels (10 100-watt).

applications, especially new systems. They are relatively cheap and should provide several years of service if treated properly. One of the things I didn’t realize when I first ordered the panels and batteries is how the solar array needs to be sized to the battery bank. You can have too large of a battery bank for the number of panels which isn’t good for the batteries. I actually was on the bottom edge with my amount of PV (photovoltaic) watts with our original number of panels (10 100-watt).

I ended up ordering more panels, 5 50-watt panels, after having received the first 10 100-watt panels for three reasons: they didn’t have any more of the 100 watt panels matching what I already received, I wanted to size the PV array more appropriately to our battery bank size, and it allows a little more available power generation for the system. As I mentioned in a previous post, conservation is the first three things you should do in setting up an off-grid system. In sizing your system, you need to be able to compute your reasonable and realistic electricity usage. This is where a Kill-A-Watt meter comes in very handy (as of 12/30/09, Newegg has it on sale for $19.99 with free shipping if you use promo code EMCMNPM27).

I ended up ordering more panels, 5 50-watt panels, after having received the first 10 100-watt panels for three reasons: they didn’t have any more of the 100 watt panels matching what I already received, I wanted to size the PV array more appropriately to our battery bank size, and it allows a little more available power generation for the system. As I mentioned in a previous post, conservation is the first three things you should do in setting up an off-grid system. In sizing your system, you need to be able to compute your reasonable and realistic electricity usage. This is where a Kill-A-Watt meter comes in very handy (as of 12/30/09, Newegg has it on sale for $19.99 with free shipping if you use promo code EMCMNPM27).

For our usage we’ve figured on the following daily consumption (rounding up each in order to over-figure rather than under-figure):

- 300 watts for refrigerator

- 300 watts for lights

- 300 watts for computer/tv/dvd player

- 200 watts for washing machine

- 100 - 300 watts for miscellaneous usage

That gives a total of 1.2 to 1.4 kilowatt hours per day. We can and probably will use less because these numbers are figured high on purpose based upon our current usage. There will be times when there is limited sun during a given week because of cloud cover, meaning there will be less electricity available for use. Extended periods of cloudy weather would probably require a generator or other power source to charge the batteries. If we weren’t trying to run a refrigerator, we could just live without electricity during such times until the sun returned to recharge the batteries. So, we’ll be getting a small generator as a backup to keep the batteries healthy – discharging batteries too low is greatly limits their lifetime.

We can figure the necessary battery size for our system based upon our general usage (let’s round it up to 1.5 Kwh). When figuring usage, watts for different voltages are equivalent, but amps are not. There’s a simple formula: volts time amps equals watts. That means at 120 volts (standard AC) 12.5 amps equals 1,500 watts (120 x 12.5 = 1,500). However, at 24 volts (the voltage of our battery bank), 1.5 kilowatts requires more amps: 24 volts times 62.5 amps equals 1,500 watts (24 x 62.5 = 1,500). If I made my calculations based upon amps, I’ be way off. When figuring battery usage, we need to be sure and use the right numbers.

So, our daily usage at 1.5 kilowatt hours requires 62.5 amp hours from the batteries. A standard three day reserve would require 187.5 amp hours. For battery health and life, it is best to not cycle it too deeply. I don’t want to use more than 20% of the battery’s capacity on a regular basis. Fifty percent is the maximum level of discharge, and I prefer not to discharge it that low. At 62.5 amp hours per day, the daily cycle of the battery will be about 10%. We could go 2.5 days without sun without going below 80% state of charge on the batteries. At 50%, we have about a 5 day reserve.

The thing that needs to be figured into all of this is the inefficiencies within the system. All of the components are not 100% efficient. For instance, it’s generally figured that batteries are only 80% efficient. At that rate, our usage figures out to just over 4 days reserve. These numbers give us a good estimate of the capabilities of our storage as it relates to usage. We’ll also have a battery monitor that will give us information regarding the battery’s state of charge and other pertinent information.

There are other inefficiencies in the system to be figured, too. One of those is the inverter. My numbers above haven’t considered the amount of power the inverter will consume just by being on. In fact, the reason we’ll have two inverters is because the smaller one will consume less power than the larger one while supplying the power we need in our home 90% of the time. I originally bought the larger one off of Ebay for about half price of new. Later, I realized that it would draw up to 576 watts per day (probably less, but, again, it’s better to figure on the upper end). The smaller 600 watt inverter will consume 250 or less watts per day.

Okay, you don’t have to do all of these computations in order to set up a system. For me they’re important in sizing our system. A lot of people start out small and build on to their system over time. This allows them to figure out what works as they build. This is a good way to learn. There are also a lot of online resources to help you learn about solar power systems. I’ve found some great information on the

Northern Arizona Wind and Sun discussion forum. A little searching will reveal a lot more information if you have the time and desire.

A nice resource for figuring how much power you can expect to realize from a solar electric system is the site

PVwatts. You can input location information and PV array specifics to figure how much electricity you can realistically generate for usage. Their numbers are based upon statistics collected over 20 years. If you want to compute for an off-grid setup, put 0.52 in the “DC to AC Derate Factor” to account for the inefficiencies in the system. I know this sounds like a large amount to derate it, but it is recommended by those with experience in order to give you realistic figures to work with. This number accounts for panel, battery, and inverter efficiencies which are less than 100% each.

So, our system will have a 1,250 watt PV array feeding a 24-volt 675 amp hour battery bank connected to an inverter that will output clean AC power for our household use. We could have designed and put together a smaller system, but we had the opportunity to make it this size at this time. As I put this together (it’s still being put together), I worked with a self-imposed budget of $5,000 (money taken out of a 403b account budgeted for building our house – the solar power system is part of the house project). In some ways that was an ambitious number, but not completely unrealistic. Our total will actually come out to about $7,000, but the federal government offers a 30% tax credit for installing a system. After that credit (yes, I’ll take it), we will fit within our $5,000 budget (I had hoped to fit within it prior to the tax credit).

We figured as long as we were able to, we ought to make the system larger than smaller. Generally, usage ends up being greater rather than smaller. At our system’s size, during the shortest month (December) we can still realistically expect to generate enough power to consume 1.5 kilowatt hours a day (based upon

PVwatts calculations). During the peak months (May, June, & July) while we have plenty of sunshine, we’ll be able to go hog wild and use up to 4 kilowatt hours a day! Ya’ll come over for the party!

I bought the panels and batteries from

I bought the panels and batteries from  applications, especially new systems. They are relatively cheap and should provide several years of service if treated properly. One of the things I didn’t realize when I first ordered the panels and batteries is how the solar array needs to be sized to the battery bank. You can have too large of a battery bank for the number of panels which isn’t good for the batteries. I actually was on the bottom edge with my amount of PV (photovoltaic) watts with our original number of panels (10 100-watt).

applications, especially new systems. They are relatively cheap and should provide several years of service if treated properly. One of the things I didn’t realize when I first ordered the panels and batteries is how the solar array needs to be sized to the battery bank. You can have too large of a battery bank for the number of panels which isn’t good for the batteries. I actually was on the bottom edge with my amount of PV (photovoltaic) watts with our original number of panels (10 100-watt).  I ended up ordering more panels, 5 50-watt panels, after having received the first 10 100-watt panels for three reasons: they didn’t have any more of the 100 watt panels matching what I already received, I wanted to size the PV array more appropriately to our battery bank size, and it allows a little more available power generation for the system. As I mentioned in a previous post, conservation is the first three things you should do in setting up an off-grid system. In sizing your system, you need to be able to compute your reasonable and realistic electricity usage. This is where a Kill-A-Watt meter comes in very handy (as of 12/30/09,

I ended up ordering more panels, 5 50-watt panels, after having received the first 10 100-watt panels for three reasons: they didn’t have any more of the 100 watt panels matching what I already received, I wanted to size the PV array more appropriately to our battery bank size, and it allows a little more available power generation for the system. As I mentioned in a previous post, conservation is the first three things you should do in setting up an off-grid system. In sizing your system, you need to be able to compute your reasonable and realistic electricity usage. This is where a Kill-A-Watt meter comes in very handy (as of 12/30/09,